Little Rock and Eisenhower

Preface

Little Rock and Eisenhower

was submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements in Gender, Nationalism, and Black Freedom, a Graduate level course, at Millersville University, spring 2008. If anyone would like to use it in their

research please email me.

John Keegan.

May 2008

Paper in Word Format

Paper in Word Format

The school desegregation crisis of 1957 in Little Rock Arkansas not only, as Elizabeth Jacoway put it, shocked the nation, it also had Constitutional and international implications for the United States Government. Because of its importance to the African-American Freedom Struggle, many historians have analyzed the Little Rock crisis from a variety of perspectives over the last fifty years. Many historians have taken a top-down approach to their analysis focusing on the politicaland Constitutional aspects of the crisis. Thus, the reaction to the Supreme Court’s Brown I and Brown II decisions of 1954 and 1955 respectively, the actions of Arkansas Governor Faubus, the federal courts, and President Eisenhower had been analyzed most often. Most of the historians reviewed for this analysis characterized Eisenhower as reluctant to support publicly the Supreme Court’s decision and slow in taking action to enforce the Court’s order.

In order to understand and analyze historians’ general conclusions about Eisenhower’s actions, it is necessary to put them in context with the events that led to and culminated in the Little Rock crisis of 1957. In May 1954, following the announcement of the decision in Brown I Little Rock's school board voluntarily initiated action in compliance with the Supreme Court’s decision. Virgil T. Blossom the new superintendent of schools developed a plan consistent with the Court's order. In essence, the Blossom plan called for the integration of all secondary schools by September 1957. The date for integrating the elementary schools remained unclear. However, by May 1955, the Little Rock school board, after the ruling in Brown II published a significantly different plan. The Little Rock Phase Program provided limited integration of only Central High School, which would not occur until September 1957 and involve only a handful of African-American students.1

At the same time, Eisenhower was reluctant to support publicly Brown I. John A. Kirk argued in his book Beyond Little Rock, that Eisenhower reluctant to voice support for Brown in public and he was disparaging of the Supreme Court’s decision in private.

2 Additionally, Stanley I. Kutler noted in Eisenhower, the Judiciary, and Desegregation: Some Reflections,

Eisenhower told his Attorney General Herbert Brownell a month after the Supreme Court handed down Brown I I don’t know where I stand, but I think that the best interests of the U.S. demand an answer in keeping with past decisions.

Kutler maintained that the statement showed Eisenhower had a marked preference for maintaining Plessey v. Ferguson as the law of the land.3 Furthermore, Elizabeth Jacoway

asserted in her book Turn Away Thy Son: Little Rock the Crisis that Shocked the Nation, Eisenhower had never been a supporter of using force to change Southern racial mores. The worsening situation in Little Rock forced him into a posture that he assumed reluctantly.

4 Finally, Tony Freyer maintained in his book The Little Rock Crisis: A Constitutional Interpretation that Eisenhower had provided little direct public support for desegregation.

5

While all of the authors illustrated Eisenhower’s reluctance to voice support for the Brown decisions and his reluctance to use force to change Southern racial values, they seem to have discounted Eisenhower’s explanation for not supporting the decisions more than he did. From Eisenhower’s point of view, the Court's judgment was law, and he would abide by it. Eisenhower believed that if he expressed publicly, either approval or disapproval of a Supreme Court decision in one case, he would be obligated to do so in many, if not all, cases. Inevitably, he would be drawn into a public statement of disagreement with some decision, creating suspicion that his enthusiasm of enforcement would be in doubt such cases. Additionally, Eisenhower held that approving or criticizing Supreme Court decisions tended to lower the dignity of the government. Eisenhower asserted that he definitely agreed with the unanimous decision.6

Furthermore, none of the authors discussed Eisenhower’s successful efforts to desegregate the public schools of the District of Columbia. However, Eisenhower in his memoirs, Herbert Brownell Eisenhower’s Attorney General in Eisenhower’s

Civil Rights Program: A Personal Assessment,

and James Duram in his book A

Moderate among Extremists illustrated his enthusiasm in enforcing Brown I. As soon as the decision was handed down, he called the District of Columbia commissioners to the Oval Office and told them the District should take the

lead in desegregating the schools as an example to the entire country.

By September 1954, the policy of desegregation had gone into effect in Washington, DC without violence.7

Additionally, Brownell and Duram also noted that in addition to desegregating DC public schools, Eisenhower also resurrected and used laws forbidding segregated facilities in the District of Columbia apparently lost since Reconstruction. Additionally, he completed the desegregation of the military, and desegregating schools on military bases. The above actions symbolized Eisenhower’s preferred method of leadership by example. Nevertheless, Duram argued that those who believed in the application of broad federal power in the area of civil liberties were increasingly disenchanted with Eisenhower’s narrow perception of those liberties and the reticence he exercised in applying them. Furthermore, Duram asserted Eisenhower had a limited conception of the scope of executive power and federal law. Most of the complexity of the desegregation problem was founded in the interaction of state and federal authority or appeared in the area, which had been reserved, to the states under their police powers. Eisenhower did not believe the power and the responsibility of the federal government extended into those areas. Thus, strong presidential leadership for desegregation in such areas proved difficult for Eisenhower to exercise. 8

Such a dichotomy leads to the conclusion that Eisenhower was of two minds on the issue of desegregation. Where he believed the federal government had the authority to enforce the Supreme Court’s decision Eisenhower did so with all

deliberate speed

and were Eisenhower did not believe the federal government had the authority he preferred to lead the states through the example he set. Regardless of Eisenhower being on both sides of the fence, Kutler argued that Eisenhower’s record

illustrated a clear commitment to enforce federal court orders equal to that of his Constitutional obligation to enforce laws. Eisenhower contrasted sharply with Andrew Jackson’s view expressed in his reaction to the Supreme Court decision

Cherokee Nation v Georgia 1830 John

Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it.

Eisenhower disagreed; holding that if people only obey the orders of the Courts when they personally approve of them the end of the American system will not be far off.9

By March 1956, Eisenhower illustrated his moderate approach in his response to the Southern Manifesto. Signed by 100 representatives and senators, it pledged to overturn the Supreme Court’s decisions on segregation. Eisenhower made clear the

manifesto said they would use every legal means to overturn desegregation. No one in any responsible position had discussed nullification, and if nullification were acted upon, the president would uphold the Constitution.

10 Duram argued that Eisenhower’s response demonstrated his unwillingness to provoke a confrontation on the issue. Additionally, Duram maintained the president softened that stance

by pointing out that the Supreme

Court acknowledged the emotions surrounding the segregation issue by holding the

process had to be gradual.

Furthermore, Eisenhower condemned those taking extreme positions on both sides, refused to place a timetable on integration, and stated that it was his intention to achieve progress without coercion.

11 However, that middle way, which relied on jawboning—influence, or pressure by persuasion rather than by the exertion of force or authority, Kutler argued, signaled vacillation and reluctance to confront the issue.12 Moreover, as Kirk asserted due to the reluctance to implement the decision, the lack of support from the legislative and executive branches, the public at large, and divisions within the Court itself, it fashioned the ambiguous and confusing

compromise of

Brown II.13

Thus, the ambiguity of the Brown II ruling made it vulnerable to legal challenges from both sides. The first challenge to Little Rock’s Phase Program Aaron v Cooper 1956 came from the local NAACP, and the African-American community,

spurred by the determination to improve educational opportunities for their children. The NAACP decided to litigate when it became clear that Horace Mann High School would open as segregated. However, Judge Miller ruled that the Phase

Program was a … reasonable start,

and any interference with the plan would be an abuse of judicial discretion so long as the defendants continue to move in good faith …

to inaugurate and make effective a racially nondiscriminatory school system.

Freyer maintained that although Miller’s decision upheld the Phase Program the case suggested to some in the community that desegregation could be legally delayed given

local conditions, thus undermining the school board’s legal justification for the program.14

Opposition to desegregation crystallized around the states’ rights theory of interposition. The theory held that a state could interject its sovereign power between its citizens and the federal Government. Freyer argued that although the doctrine lack binding force in Constitutional law, many Americans viewed it as a way to delay or circumvent desegregation. Thus, from mid-1955 to mid-1956 Arkansas segregationists forced the theory to the center of public debate making it a political issue. Additionally, Freyer maintained that Governor Faubus was aware that any explicit endorsement of desegregation could be politically disastrous. Especially in light of Eisenhower’s refusal to take a strong stand favoring federal responsibility for the enforcement of Brown, thus placing state authorities in the position of having to enforce it. Eisenhower’s inaction meant that southern officials faced voter disapproval if they mishandled desegregation. Furthermore, in order for Faubus to pass his legislative agenda he needed the assistance of East Arkansas legislators many of whom supported segregation.

It was in order to win the democratic primary in 1956 that Faubus embraced the doctrine of interposition. Until late January 1956, Faubus had considered the theory impractical and hollow, for the Federal Government possessed greater power.

However, by late January Faubus realized that 85 percent of the people opposed desegregation, and if it did happen, it would be a slow process.

15 Thus, Governor Faubus adopted

the doctrine of interposition out of political expediency rather than conviction. Freyer argued that by August 29, 1957 Governor Faubus had linked interposition to possible violence. That is, if the Phase Program were allowed to proceed,

Faubus feared violence would ensue, thus desegregation could not proceed. However, Faubus provided no evidence to support his fears. Furthermore, Freyer maintained that Faubus placed the National Guard on alert with explicit orders to

keep the African-American students out of Central, which was what they did on September 4, 1957. At that point, Governor Faubus was in violation of a federal court order.16

Whether it was referred to as interposition or nullification depended upon which side of the issue one advocated. From Faubus’s political point of view, interposition was a position he had to support. On the other hand, Eisenhower, as stated above rejected a state’s rights to nullify federal law or court orders. However, Faubus took Eisenhower’s customary caution; not wanting to make any mistakes in a hurry, as a sign that the president could be open to compromise. By September 4, 1957, it was clear that while Eisenhower wanted to give the Arkansas Governor every possible means of retreat provided he complied with the court order, it was also clear that Eisenhower would neither compromise nor capitulate.17 Because, aside from the fact that Faubus had violated the federal court order, the Little Rock crisis was also damaging American foreign policy.

Jacoway argued that almost from the beginning of the crisis Eisenhower was under enormous international pressure, for the crisis demonstrated the seeming inability of the United States to secure the blessings of liberty for all its citizens.18 Cary Fraser in his article, Crossing the Color Line in Little Rock: the Eisenhower Administration and the Dilemma of Race for U.S. Foreign Policy,

illustrated that Secretary of State John Foster Dulles advised Eisenhower this situation is ruining our foreign policy.

The effect of this in Asia and Africa will be worse for us than Hungary was for the Russians.

Additionally, Fraser argued that international reaction to the crisis was a factor in the domestic decision-making process. Eisenhower understood the harm

the crisis was causing to the prestige, influence, and safety, of the nation around the world.19

However, not wanting to make any mistakes in a hurry, Eisenhower delayed federal intervention until Judge Davies had an opportunity to study the results of the FBI investigation. Freyer made clear that:

The Justice Department's findings went against Governor Faubus on almost every point. The FBI inquiry turned of documentary proof that explicitly ordered that the National Guard keep African-American children out of Central. The report also stated that the governor's claims about excessive weapons sales were groundless or at best based on a rumor, and no local officials had sought the governor's intervention.20

At that point, Kutler argued that Eisenhower was persuaded by his advisers that he had no alternative but to confront Faubus and, if necessary, demonstrate his resolve with armed intervention.

21 Nevertheless, Eisenhower made one final attempt at jawboning. Governor Faubus through an intermediary had requested a meeting with Eisenhower, which Eisenhower granted at the Naval Air Station in Newport Rhode Island on September 14, 1957.

Eisenhower and Faubus met privately for about twenty minutes, no aides recorded the conversation. The only surviving accounts come from the two participants. Of the two authors that recount the meeting, Jacoway and Duram, Jacoway relied on Faubus’s account more than Eisenhower’s. In essence, Eisenhower told Faubus that when the governor went home he should change the orders of the National Guard such that it continued to preserve order, but allow the African-American children to attend Central High School. According to Governor Faubus, he repeatedly assured the President that he was a loyal citizen, and he recognized the supremacy of federal law and courts. Finally, Eisenhower expressed to Faubus that he did not believe that a test of power between the President and a governor was beneficial to anyone, for there would only be one of come the state would lose. Eisenhower had the impression that Faubus would return to Arkansas and change his orders to the National Guard. At a press conference at the conclusion of the meeting, Eisenhower praised Faubus for his promise to respect the orders of the federal court. However, at no point in Faubus’s statement did he refer to any commitment to change the orders of the National Guard.22

Jacoway asserted that Faubus later claimed consistently he never gave Eisenhower those assurances. Furthermore, neither of the memoirs of Brooks Hays or Sherman Adams reported such assurances. She concluded it was likely that the man who cultivated a pattern of smiling and nodding and seeming to agree without specifically committing himself, caused a man who was accustomed to having his orders obeyed to conclude that he had carried the day.

Jacoway’s conclusion suggests that Eisenhower misinterpreted Faubus’s responses. Additionally, in her notes, Jacoway asserted three weeks after the Newport conference, after many emotional events had transpired, Eisenhower dictated his notes about the visit with Faubus.

23 That suggests the Jacoway believed that Eisenhower's recollection of the meeting was distorted by his emotions. However, both Eisenhower in his memoirs and Faubus in his account stated that the governor repeatedly told the President, he

recognized the supremacy of federal law and courts. Therefore, it was completely logical for Eisenhower to conclude that Faubus would, after Eisenhower's admonishment, revoke his orders to the National Guard. Because that was what a governor,

who respected federal laws and court orders would do if he were honest. Furthermore, Jacoway’s suggestion overlooked the fact that he was Supreme Allied Commander during the invasion of Normandy, and until the end of the Second World War

Eisenhower was under tremendous emotional stress on a daily basis. Once that is taken into account, it is more likely that Faubus did in fact go back on his word.

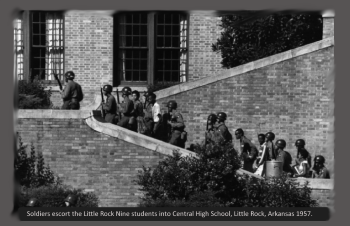

On September 24, 1957, the African-American students entered Central, but due to disturbances inside and outside the school, they withdrew. Instead of simply depending on a federalized Arkansas National Guard or sending the U.S. marshals that school officials and the mayor requested, Eisenhower sent in the 101st Airborne. By that action, Eisenhower not only upheld a court order, but also reassured foreign governments that his administration was committed to enforcing the authority of the federal government, including the use of troops, to protect the rights of African-Americans.24 However, Freyer asserted that the shortsightedness of sending in federal troops forced Faubus to adopt an outright segregationist stance, which prolonged the conflict until 1959.25

That assessment was puzzling; it suggests that a federalized Arkansas National Guard could be trusted to carry out Eisenhower’s orders. In fact, the National Guard had demonstrated its inability to be trusted by carrying out Governor Faubus’s unlawful order to keep the African-American students out of Central. Additionally, U.S. marshals could not have been used for much the same reason, for if the National Guard backed Faubus there would have been little the marshals could have done. The only way to ensure compliance and restore order was the use of federal troops. While the presence of federal combat troops restored order, it did not resolve the conflict that was left to community leaders and the school board with the assistance of the federal court. Even then, students in the Little Rock school system had to endure a year without school and another Supreme Court case Cooper v. Aaron 1958.

While most historians reviewed for this analysis viewed Eisenhower’s cautious moderate approach to desegregation as reluctance to act, they also made clear that when Eisenhower had to act, he acted decisively. In the end, despite the loss of a school year, the crisis was resolved at the local level, where Eisenhower thought it should be. Whether Eisenhower should have acted earlier or differently is debatable. However, it is clear that Eisenhower’s actions were based, unlike Governor Faubus’s, on strongly held convictions, and not political expediency. It is also clear that Eisenhower went to extraordinary lengths to avoid the use of force and only did so after he had no other alternative.

Notes

Eisenhower, the Judiciary, and Desegregation: Some Reflections,in Eisenhower: A Centenary Assessment, ed. Stephen E. Ambrose and Gunter Bischof (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1995), 89. 4 Elizabeth Jacoway, Turn Away Thy Son: Little Rock, the Crisis that Shocked the Nation. (New York: Free Press, 2007), 126 5 Freyer, 99 6 Dwight D. Eisenhower, The White House Years: Waging Peace 1956-1961. (New York: Doubleday, 1965), 150. 7 Eisenhower, 150, Herbert Brownell,

Eisenhower's Civil Rights Program: A Personal Assessment.Presidential Studies Quarterly 21.2 (1991): 235; James C. Duram, A Moderate Among Extremists: Dwight D. Eisenhower and the School Desegregation Crisis. (Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1981), 56. 8 Duram, 57 9 Kutler, 89 10 Eisenhower, 151 11 Duram, 126-127 12 Kutler, 91 13 Kirk, 100 14 Freyer, 57-58 15 Freyer, 74-78 16 Freyer, 103-104 17 Freyer, 105 18 Jacoway, 139 19 Cary Fraser,

Crossing the Color Line in Little Rock: the Eisenhower Administration and the Dilemma of Race for U.S. Foreign Policy.Diplomatic History 24.2 (2000): 247. 20 Freyer, 121-122 21 Kutler, 91 22 Eisenhower, 166; Duram, 148-150; Jacoway, 148 23 Jacoway, 399; note 5 24 Fraser, 247 25 Freyer, 108-109